EQUIMANITY

The horses of Leonardo da Vinci, George Stubbs, and Alex Colville have always fascinated Susan because it seemed that, although they drew and painted superbly from life they didn’t always depict horses with anatomical accuracy. And yet, the horses have an undeniable presence and energy. Wondering if the works would have the same power if the horses looked more realistic, she decided to re-create them with her own version of the horse.

Following three years of research into why each of these artists portrayed their horses as they did, this show, with its accompanying thesis, is the result. Equimanity is a word that she has coined to describe the communication, respect, trust and understanding between a person and a horse.

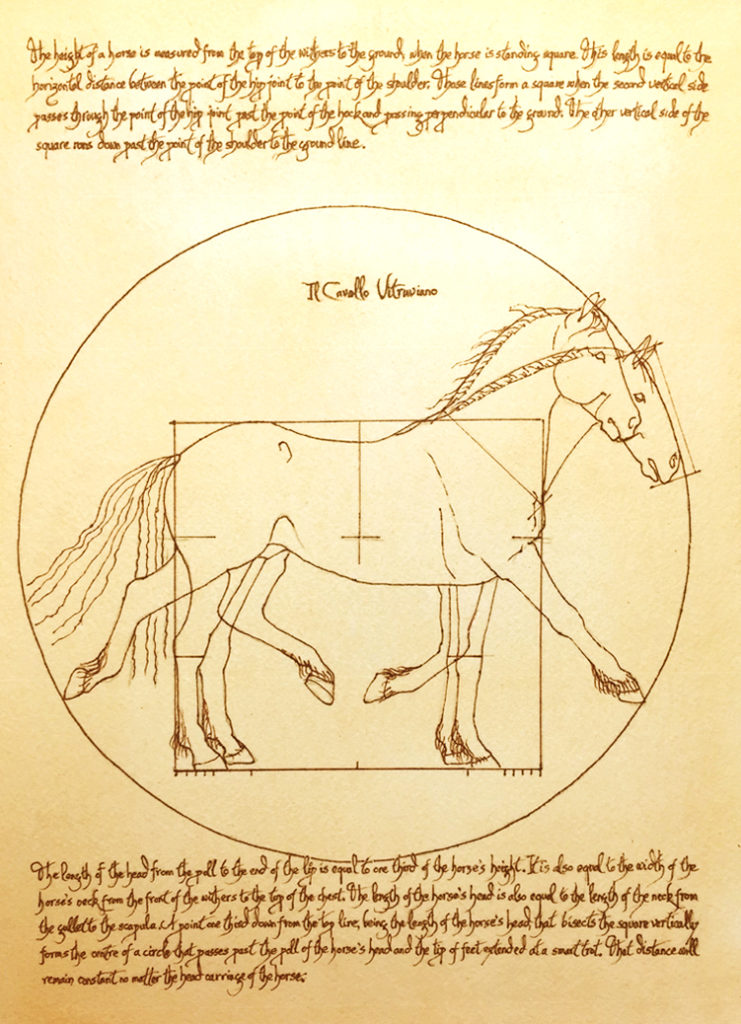

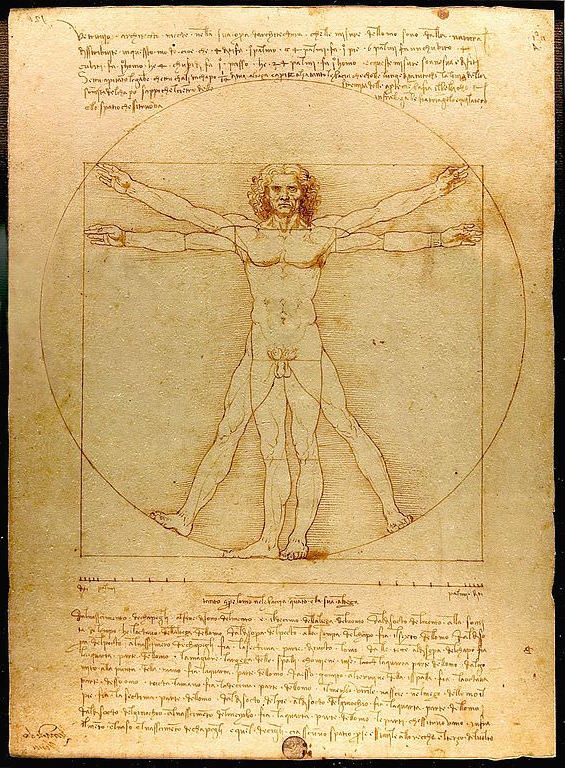

Vitruvian Horse & Vitruvian Man, da Vinci, c1487

While there is no such thing as an “ideal” horse, the equine body also has an essential symmetry, and it was a fun exercise to see how the conformation of a standing and a moving horse could fit into a square and a circle in a similar way. I think that da Vinci believed that just as man is a part of nature, and not a superior being in it, so is the horse. Hopefully, Vitruvius would have approved.

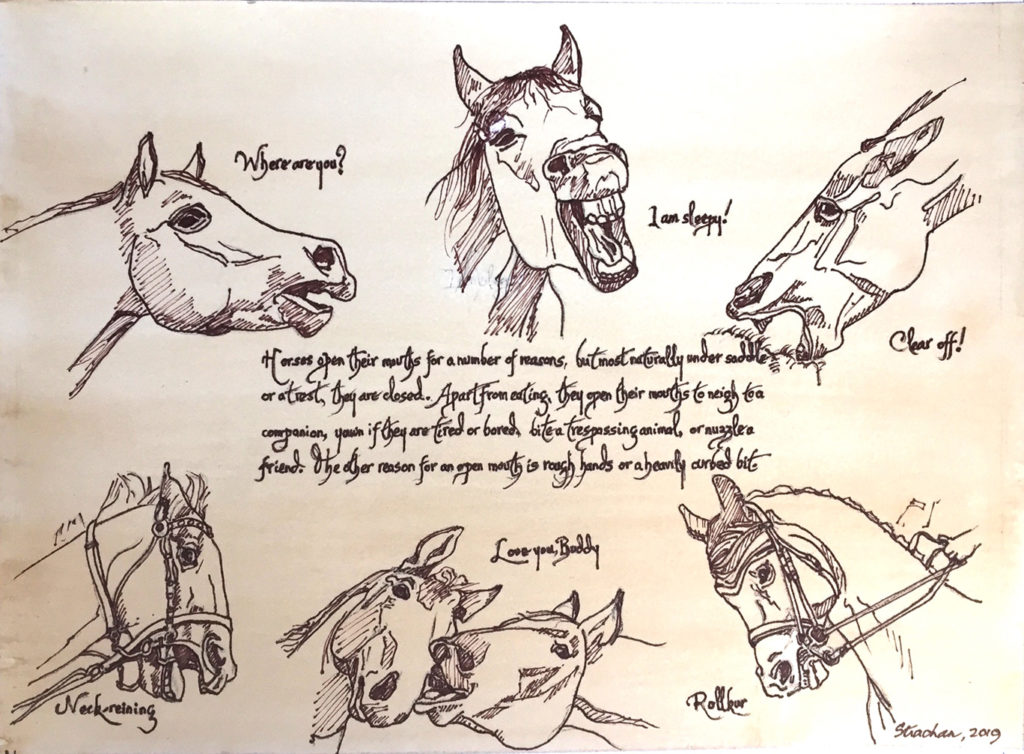

Horses With Their Mouths Open & Study of Horses for the Battle of Anghieri, da Vinci, c1504

Other than to eat, horses open their mouths only to neigh, yawn, nuzzle a friend, or bite. In all of these instances, however, the horse’s neck is extended, and not tucked into their necks, as shown by da Vinci.

Da Vinci’s horses always look as if they are in pain. My theory is that it was the equitation practices of da Vinci’s time, in particular the use of severe bits, that caused him to portray horses with their mouths open. As an engineer, he invented many machines that were used in war, but I believe he hated the use of the horse in war, and the cruelties they were subjected to. I think he portrayed his horses this way as a protest: he may have been the world’s first animal rights’ activist!

Friesian Stallion Showing Off & Study of a Horse’s Head, da Vinci, c 1504

A horse can naturally arch his neck and bring his head close into his neck, especially when he is “showing off.” Here is a drawing I made from a photo of the head of a Friesian, compared to a drawing from da Vinci’s sketchbook.

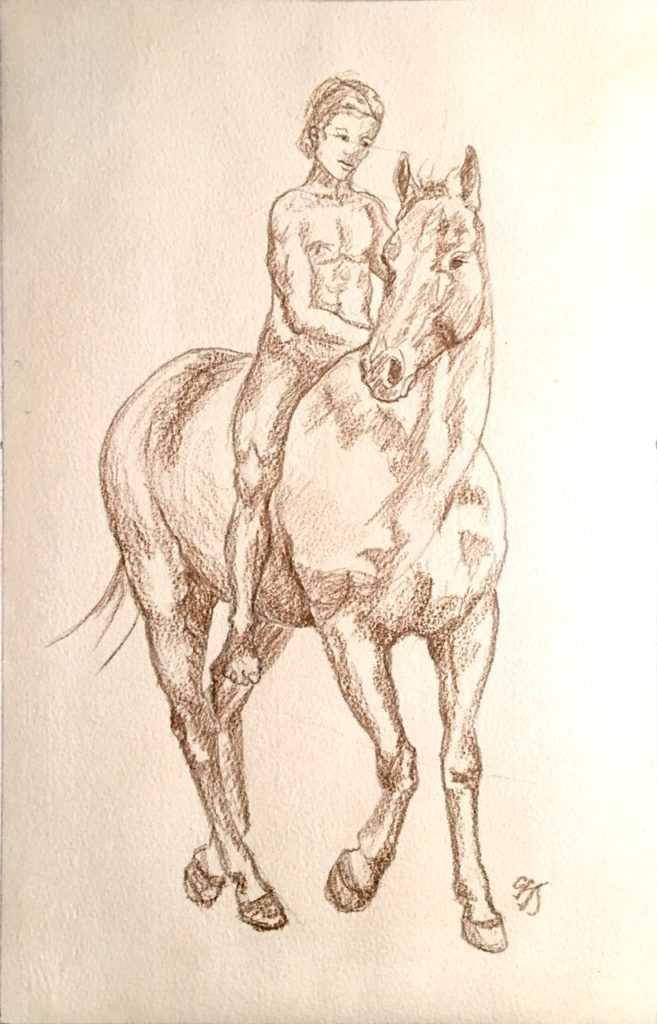

Boy on a Horse & Horse and Rider, da Vinci, 1481

Although the conformation is not quite right, Horse and Rider shows a near perfect fluidity between man and horse. The horse’s movement is a little unlikely, leaning one way while seeming to move the other way. His ears are pricked and he doesn’t look alarmed, so he is not shying away from something. While the rider is sitting too far forward, yet the two are one; the horse is relaxed, and the mouth is just barely open.

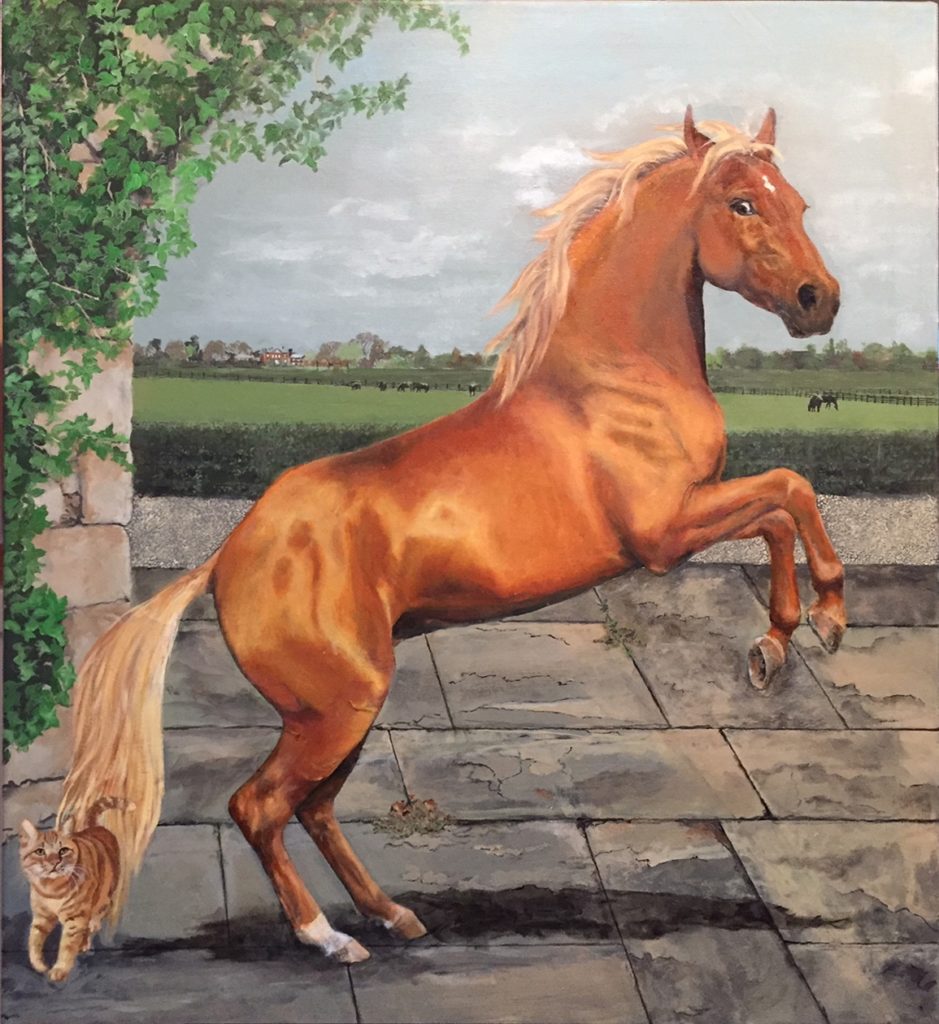

Whistlejacket Re-imagined & Whistlejacket, George Stubbs, c1764

This research on this one took me to London’s National Gallery several times, and also to Vienna’s famous Spanish Riding School! I studied the pose, the drawings of his Anatomy of the Horse, self-published in 1742, and I finally concluded that Stubbs had captured the character of the horse perfectly, who was said to have had “a nearly ungovernable temper.” The most difficult thing for Stubbs was to paint from life a horse that wouldn’t stand still, over 100 years before the invention of photography.

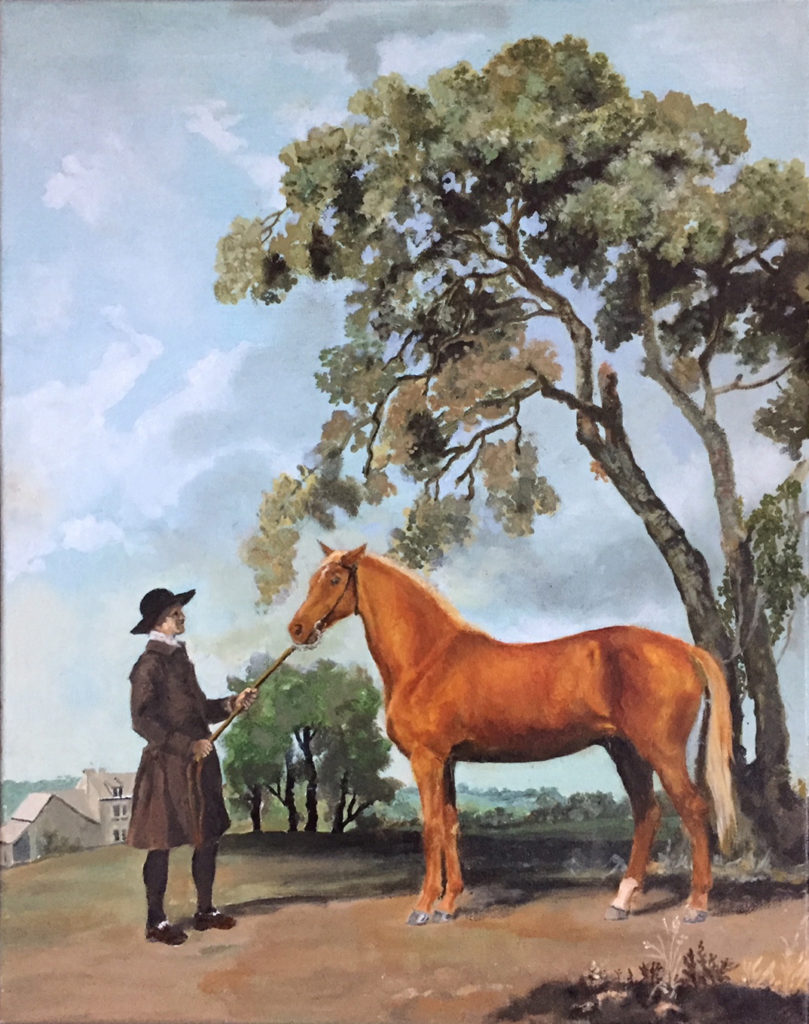

Whistlejacket Re-imagined at Grosvenor’s Stud & Lord Grosvenor’s Arabian, Stubbs, 1765

Whistlejacket was called an Arabian, a term that in the 18th century applied to any horse from “Arabia” (the Middle East).

However, Stubbs knew what a true Arabian looked like, as evidenced by his painting of an Arabian at Lord Grosvenor’s stud. The horse in this painting resembles a modern day Arabian, whereas his painting of Whistlejacket does not.

An Arabian has only 17 pairs of ribs, whereas most other breeds have 18 sets, giving the former a shorter looking back. They also have a “dished” face, and tend to have a higher head carriage and a higher set tail. I chose to paint Whistlejacket more like his ancestor on his dam’s side, the Byerley Turk, who I think looked more like the modern day Akhal Teke.

Whistlejacket Re-Imagined with two other Stallion & Whistlejacket with Two Other Stallions, Stubbs, 1762

Two years before painting him on his own, Stubbs painted Whistlejacket with two other stallions owned by Lord Rockingham. Here he has a lanky look, and his back appears longer without the cresty neck. I have shown the horses in my version as a modern Arabian (the dark bay), a modern Thoroughbred (the red bay), and an Akhal Teke, which I think he probably resembled.

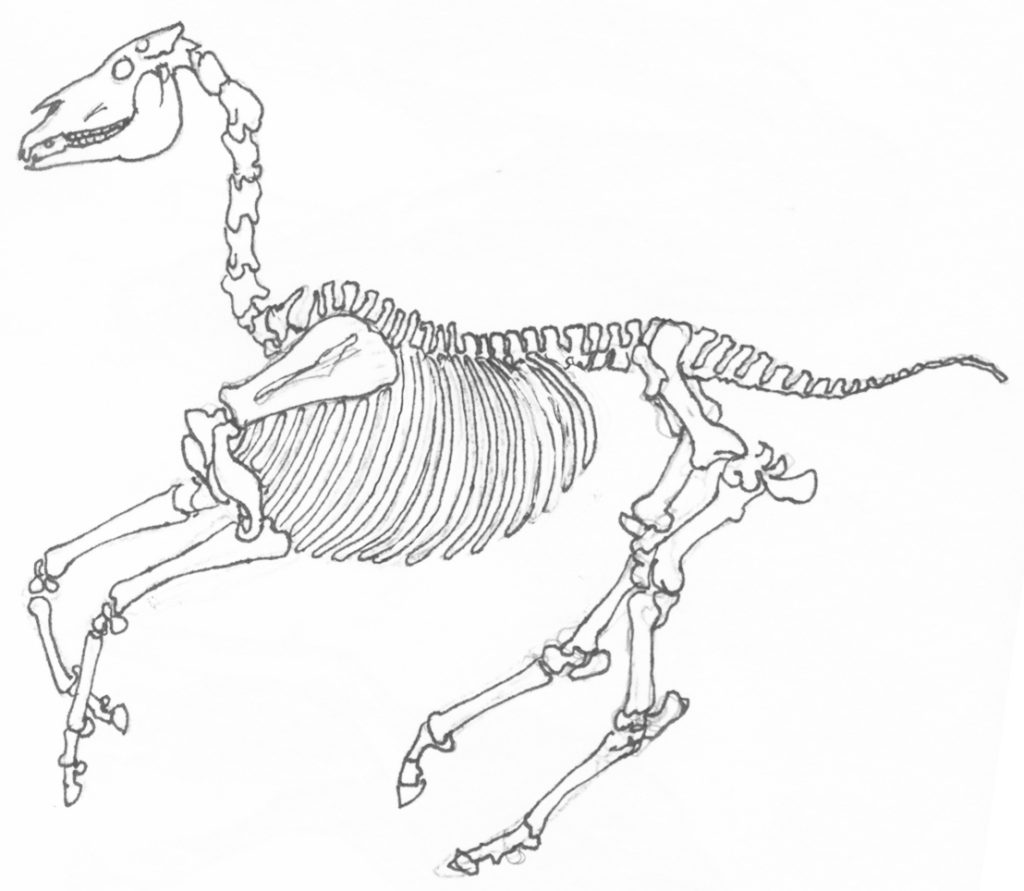

Black Horse in a Churchyard, after Alex Colville & Skeleton of Church Horse’s footfall

Colville’s Church and Horse (1964) is a conscious reference to the horror and shock of President Kennedy’s assassination in 1963. While watching the funeral on television, Colville was struck by the restless behaviour of Black Jack, the riderless horse in the funeral cortège.

I believe Colville’s horse is intended to symbolize powerlessness, fear, and lack of knowing where to go next. But it bothered me that Colville, who could draw and paint so brilliantly from life, had not made the horse more lifelike. For copyright reasons, we cannot show Colville’s actual painting, but here is a drawing of the horse’s footfall, showing that the horse is not galloping.

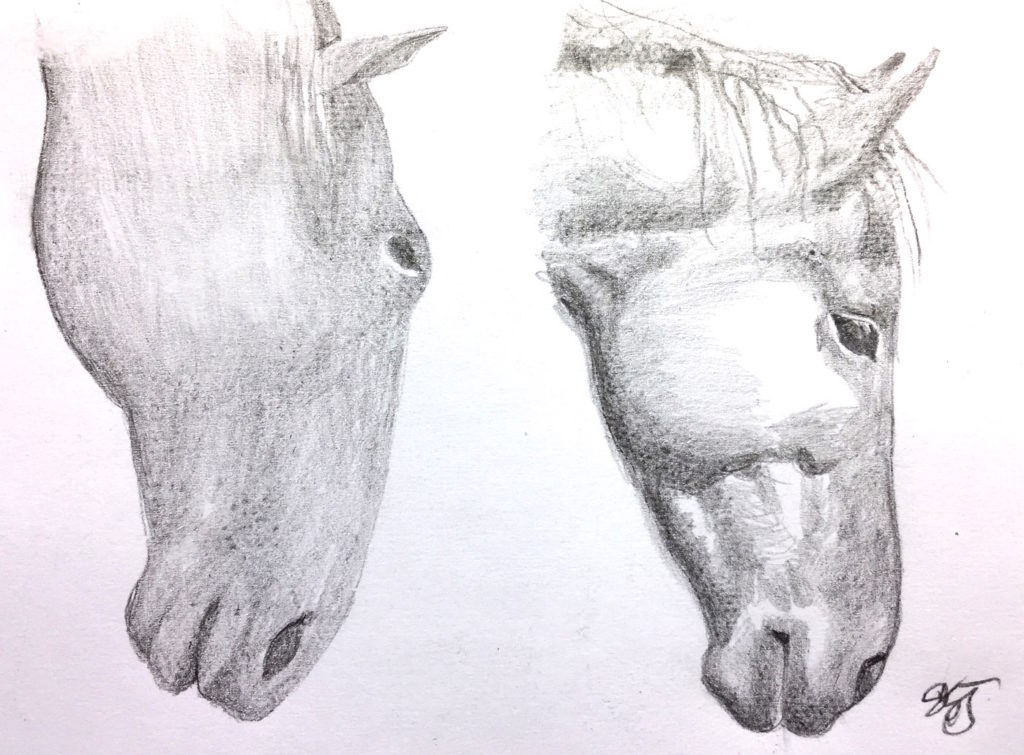

Horse and Dog, after Colville & Colville’s horse head vs more lifelike head

Dog and Horse (1953) is a painting curators rarely talk about because it isn’t about foreboding or death or the march of time. Here Colville has painted something entirely peaceful, a contented and trusting relationship between a horse and a dog.

I wanted to re-paint this painting because the horse’s head and movement is not horse-like. The eyes are forward in the head, the forehead is large, and the mouth is small. These features show Colville’s innate, or perhaps intended tendency to human-like characteristics. Also the footfall shown is not how horses walk (or graze). Colville’s horse is not a particular horse, but an ideal horse: peaceful, unthreatening, and a thinking being.

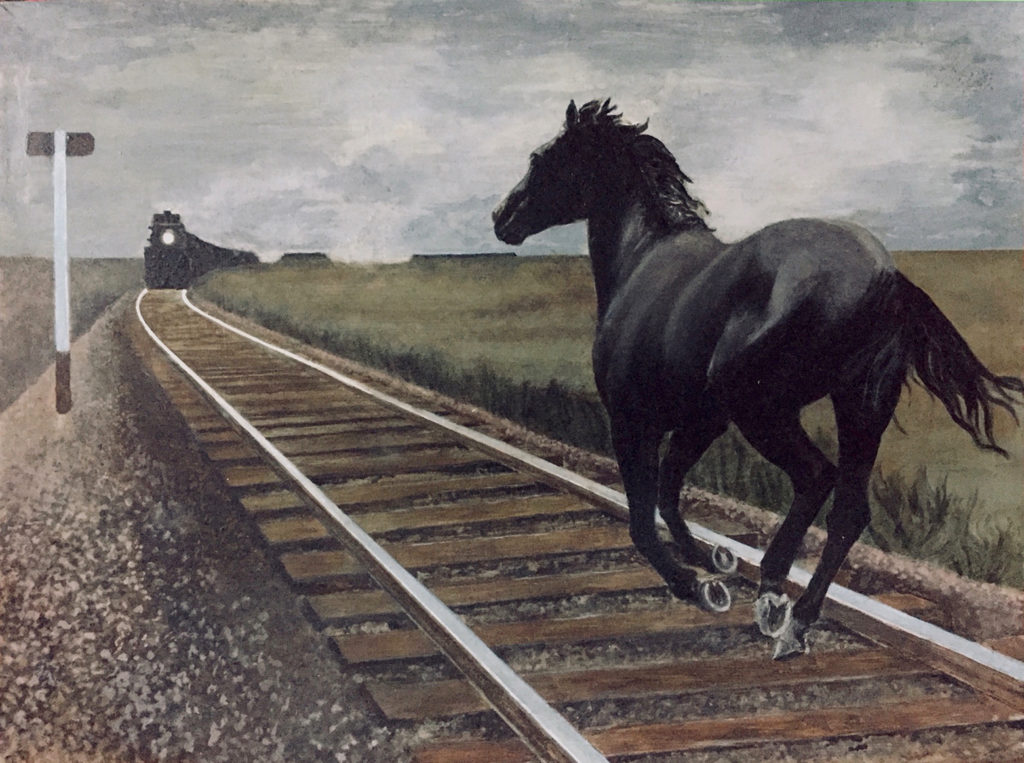

Dark Horse and Oncoming Train & Sketch of Horse from Horse and Train

Referring to his iconic painting Horse and Train (1954), Colville is quoted as saying “this painting is the skeletal key to all my paintings.” Inspired by a quote from a poem by Roy Campbell (“against a regiment I oppose a brain and a dark horse against an armoured train”), it is about the world needing some entity, a “dark horse” to come out of nowhere and make the ultimate sacrifice to derail/end the war machine.

Campbell’s poem (1946) was itself inspired by a phrase from Strange Meeting (1918), a poem by Wilfrid Owen): “And none shall break rank though nations trek from progress.” An army cannot function if one link in the chain of command is broken.

Colville didn’t paint a real horse, or a real armoured train. But my admiration of this painting is still marred by the oddness of the “phantasmagorical” horse, so I wanted to paint a real black horse, to see if it gave the same message.

Horse Hug & Horse Kiss

Having a good relationship with a horse is a partnership, a communication that runs from one to the other. When both man and horse are experiencing the world around them from different perspectives, like the thrill of racing or clearing a large jump, working in harmony is a bond that transcends language.

It’s a physical and emotional communication, which is why horses are also so good at the job of providing physical and emotional therapy. A horse will react in the same way to a human, whatever his physical or challenges or limitations may be.